Review written by Laura A. Murray-Nerger (Molecular Biology, G6)

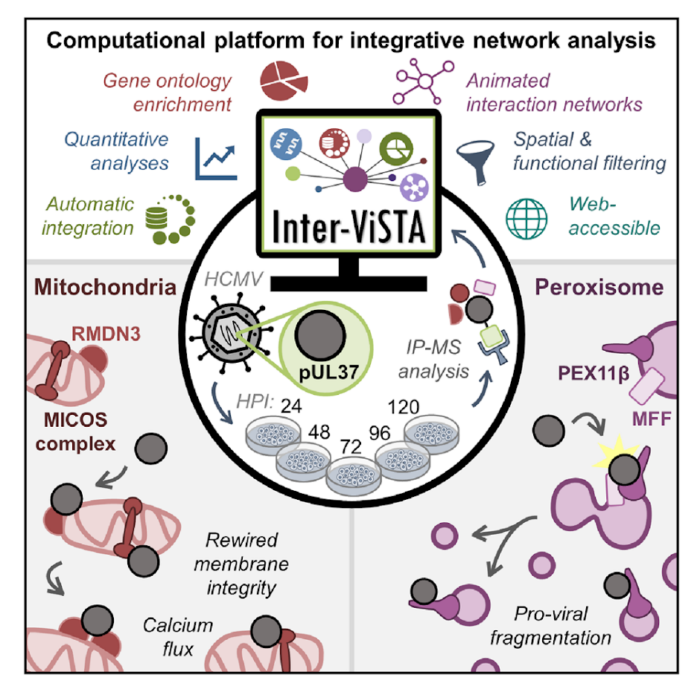

As primary and secondary school students, we learn that cellular organelles have specific functions. For example, the mitochondria is often called the “powerhouse” of the cell because it makes energy that drives other cellular processes. However, we often don’t learn about the multifaceted functions of these well-known organelles or learn about some of the less-well studied organelles, including the peroxisome. Moreover, as we learn about the functions of these organelles, it is easy to forget that they are filled with many proteins, each of which participates in a variety of functions. Importantly, these proteins do not work in isolation, but rather by interacting with each other, which creates a complex network of protein-protein associations that ultimately determine cellular fate. In their recent paper, the Cristea lab has built a computational platform that can be broadly used to assess the changes in protein-protein interactions in any biological context. They employ this newly developed tool to understand the protein-protein interactions that underlie alterations in mitochondrial and peroxisomal function during viral infection.

Continue reading