Review written by Leon Mait (PSY)

In times of financial hardship, low-income individuals can often turn to their communities for support. Unfortunately, this buffer against financial difficulties provided by community resources can erode over time. One factor that may contribute to such erosion is economic inequality (which has been on the rise in the United States). This connection was recently found by a group of international researchers, including Princeton’s own Elke U. Weber, who holds joint appointments in Psychology, the School of Public and International Affairs, and Engineering.

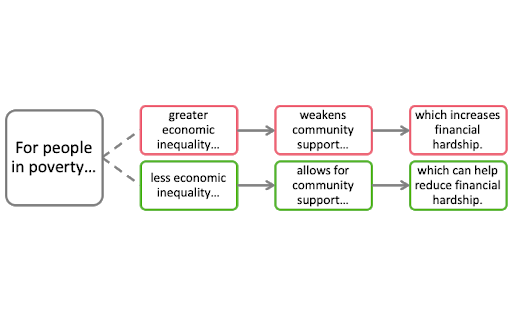

Weber and her team utilized numerous data sources and research methods across multiple studies—including surveys and experiments—to tackle the question of how economic inequality impacts financial hardship. They proposed that economic inequality is not uniformly detrimental, but rather specifically exacerbates the financial struggles of those at the lower end of the income distribution. Their reasoning: people in poverty are generally more inclined to rely on those around them when the going gets tough. But extreme inequality can undermine this support system, and thus, the going gets even tougher.

The first step in finding support for their proposal was establishing that economic inequality and financial hardship go hand-in-hand for those living in poverty. Social scientists can establish such a relationship in a number of different ways. For example, Weber and her team analyzed the responses from two different surveys—one from the CDC and one they themselves conducted online—which gave them data on over 110,000 Americans. The researchers found that respondents from more unequal counties reported experiencing more financial hardship than those of similar socioeconomic status (as well as other demographic variables like age, gender, education) in more equal counties. Importantly, this association was only present among low-income respondents, but not median- or high-income ones.

However, simply finding this relationship does not establish causality (i.e., correlation does not equal causation). One way to substantiate that it really is inequality leading to financial hardship, and not the other way around, is to vary levels of inequality. Specifically, if people are subjected to varying levels of inequality, how much financial hardship do they then feel? Because varying actual inequality is difficult in the real-world for ethical and logistical reasons, the research team tackled this second question by running an experiment where they manipulated people’s perceived inequality. Participants were divided into two groups: some were told their ZIP code has high economic inequality (specifically, that the richest 10% earn 60 times more than the poorest 10%) and others that it has low inequality (that the rich earn only 4.5 times more than the poor). Indeed, participants in the high-inequality group reported more financial hardship than those in the low-inequality group, but only participants who came from low-income households showed this difference.

While this seems convincing, an online experiment lacks “external validity”, where the results may not match what’s actually going on in the real world. Therefore, the researchers conducted a third study where they analyzed a multi-year Australian survey that collected data on household income and the labor market, allowing them to retroactively examine the effects of real-world changes. Between 2014 and 2017, the Australian government increased the tax rate for the highest-income earners, which effectively reduced economic inequality during these years. Weber and her team found that outside this period, when inequality was relatively higher, low-income Australians reported experiencing more financial hardship than during this 2014-2017 period. This pattern was again not found at the median- or high-income levels.

Altogether, these different studies included over 450,000 participants across different contexts, and they all pointed to the same conclusion: as economic inequality increases, so too does the financial hardship of people in poverty. With substantial evidence to support this claim, the researchers then investigated what mechanism might underlie this finding.

To do so, they conducted additional surveys, giving them data on a total of over 575,000 people. The team asked people questions to get a sense of how much community support they received, such as “When I run into financial difficulties, I can rely on others to support me.” No matter how the researchers measured economic inequality—by analyzing actual ZIP-code-level economic data, asking participants to estimate their local level of inequality, or making participants believe they lived in a high-inequality community as in the experiment described earlier—they always found the same pattern of results. It also didn’t seem to matter where the survey was conducted, since the researchers used survey data collected in both the U.S. and Uganda. Higher inequality was consistently associated with not only financial hardship, but also weaker community support among lower-income individuals. More importantly, this weakened support seemed to actually drive financial hardship.

The researchers couldn’t specify how this happens—why exactly inequality weakens community support and thereby worsens hardship—but they did offer some speculation. One idea is that inequality is associated with a greater sense of competitiveness, and feeling that others pose a threat to you. This would make people much less inclined to reach out to their neighbors for help. But a strong sense of community can reduce anxieties about inferiority or stigma when people are struggling. In fact, in a supplemental study the team ran, people who reported greater community support were less likely to believe they would be made to feel ashamed for seeking financial help. So in addition to inequality’s material barriers, low-income individuals also have to overcome its psychological ones.

These findings ultimately suggest a vicious cycle: as inequality increases and the relative share of wealth at the low end of the income distribution shrinks, people are less likely to turn to their communities for support. This further reduces their wealth, and in turn exacerbates inequality. Weber and colleagues’ studies collectively emphasize the importance of the community for those living in poverty. However, individuals have to actually perceive their community as a source of support to reap its benefits. Therefore, Dr. Weber and her research team call on policymakers to commit to supporting not just low-income individuals, but low-income communities as a whole.

The original article was published in Cell on March 30, 2020. The full version may be found here.