Review written by Liza Mankovskaya (SLA, G7)

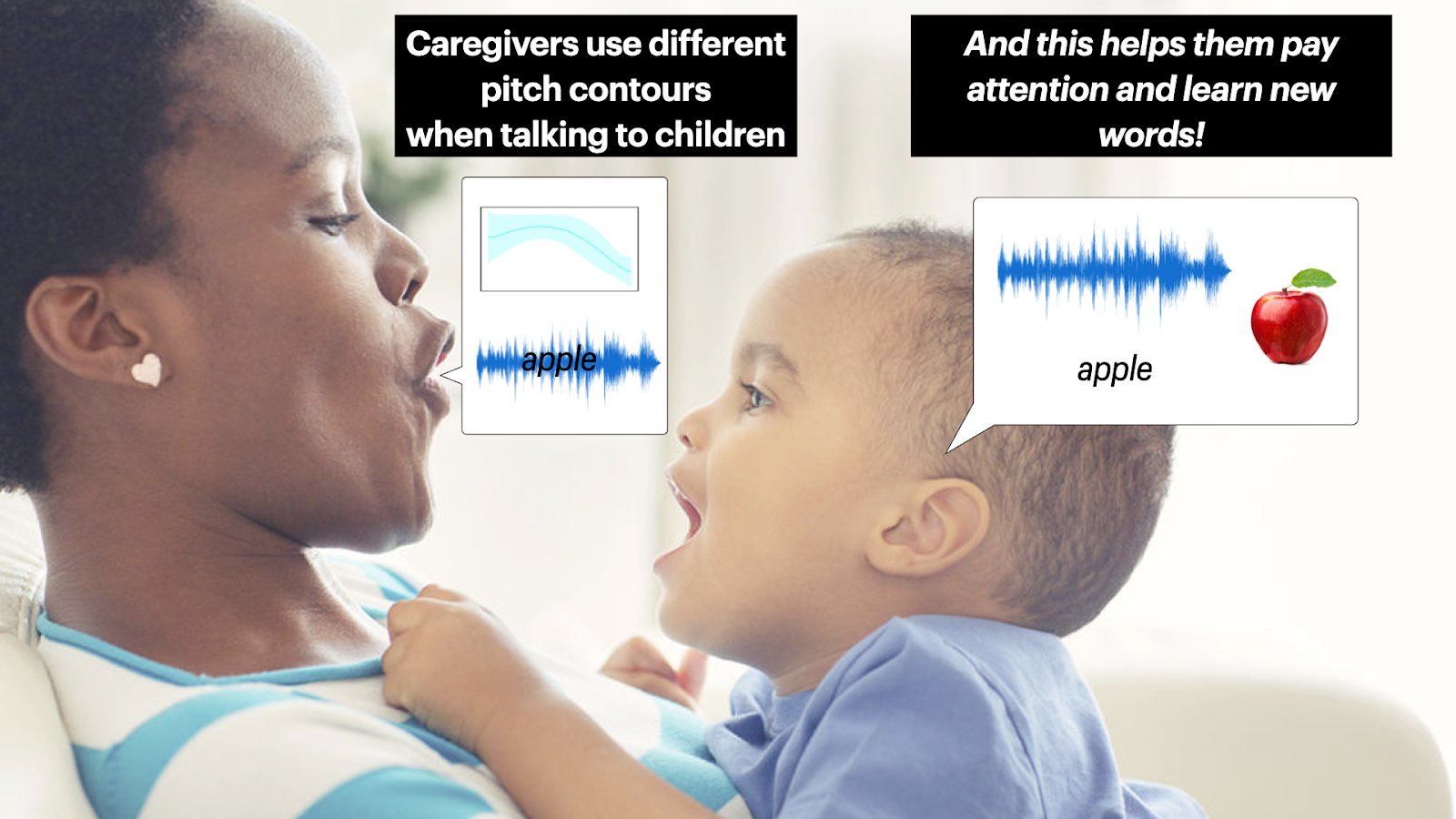

Have you ever wondered why we tend to talk to children in a different way than we speak to adults? You might think there isn’t much to it. After all, kids are cute, so adults melt, and hence – “baby talk.” Yet, this difference serves a very important purpose. Several decades of studies have shown that children, from young infants to toddlers, prefer this kind of speech; most importantly, when exposed to speech directed to them in this way, children are more engaged and learn more. But why? We can first consider the differences between speech to children, and speech between adults. One of the most recognizable ways in which caregivers tend to speak to children–child-directed-speech (CDS)–is characterized by significant variation in pitch and intonation. Compared to CDS, “adult” voice and intonations are much more monotonous, so children have a harder time concentrating. Thus, researchers believe that the overall higher level of engagement engendered by CDS promotes learning in children. What is less known, however, is how children process and learn from specific patterns of stress and intonation of CDS on the level of individual words. Recently, Princeton researchers Mira Nencheva, Elise Piazza, and Professor Casey Lew-Williams in the department of Psychology took on exactly this question. They identified specific ways in which caregivers’ pitch changed throughout a word (pitch contours) of CDS in English and analyzed how engaged two-year-old children were during these different pitch contours and how well they learned novel words that followed these contours. Their findings provide a sub-second frame for understanding the mechanisms and features of CDS that make it optimal for children as they listen to CDS in real time.

To understand “the recipe of success”–meaning the features of CDS that are optimal for learning when children are really engaged–the team needed to investigate several things. First, they wanted to study and describe specific pitch patterns on the level of words in CDS. Then, they needed to measure children’s engagement for the main patterns they identified. Finally, they wanted to know which pitch patterns resulted in the best learning outcomes; that is, which patterns led to the child remembering a novel word best. To investigate all of this, the team conducted three sets of experiments.

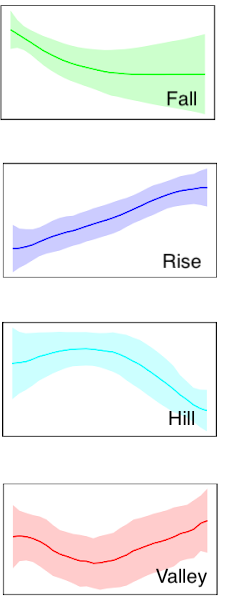

First, the researchers selected two large sets of transcribed and recorded natural CDS from CHILDES database (one of a mother addressing a 6–12-month old infant and the other of two mothers addressing 24–30-month-old children). Then, they used a statistical analysis called hierarchical clustering to group nouns with similar pitch contours into four main intonational shapes. Based on whether the speaker’s intonation fell or rose during a word, the researchers termed these pitch contours respectively: ‘falls’ (the voice goes down), ‘rises’ (up), ‘hills’ (up and then down), and ‘valleys’ (down and then up, see Figure 1. The audio files of pitch contours are also accessible here).

In the second experiment, the team focused on how toddlers react to these four main ways that pitch changes over the course of a word in CDS. To do that, they tested how engaged two-year-old children were while listening to words pronounced in each of the four contours. In this experiment, Nencheva et al. developed a novel solution to the problem of reliably tracking children’s attention on such a fine timescale. Traditionally, what is measured in similar CDS experiments is how long a child listens to a stream of auditory information. Yet, in this approach, there is no good way to know the dynamics of engagement over time and it is challenging to measure engagement peak(s). As their goal was to understand precisely the moment-to-moment changes in children’s attention span, Nencheva et al. decided to employ the method of pupil synchrony.

The pupil synchrony method measures how engaged an individual is with a given task based on whether their pupils dilate in response to a task-relevant stimulus, such as listening to a story. For example, if the task is listen to the story and we are paying attention to it, our pupils would dilate and constrict in response to specific moments in that story (e.g. changes in emotional content, auditory features, etc.), whereas if the same story is played to us but we are not attending to it, our pupil dilations would not be tied to the changes in the story (instead they may be responding to our internal thoughts or other things we’re paying attention to). If we record the pupil responses of multiple listeners who were listening to and paying attention to a specific segment in the same story, their pupil responses would likely be very similar at that specific moment in time, indicating their shared attention at that moment in the story. The authors refer to this measure of similarity of pupil responses during a specific segment of speech as pupil size synchrony.

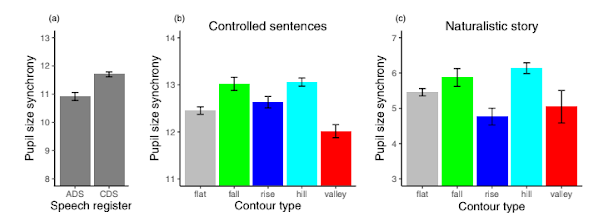

This method has been well-tested in adult studies on narrative comprehension but this is one of the first applications to study attention in children for CDS. The team tested the method by exposing children to a story accompanied by visuals, first in CDS and then in adult-directed-speech. The level of pupil size synchrony, a proxy for overall engagement with the story, was higher during CDS (Figure 2a). Next, the team tested individual sentences to understand the moment-to-moment engagement with various pitch contours of CDS. The result? The most and the least engaging pitch contours are the “hill” (the voice goes up and quickly down) and the “valley” (gradual elevation), respectively. Thus, the researchers for the first time measured the dynamics of how children’s engagement varies depending on whether they’re listening to CDS vs. adult speech. Most crucially, they found that there are specific pitch contours that are related to heightened engagement.

Finally, in the third experiment, the researchers wanted to know whether higher engagement with a pitch contour, as indicated by high pupil synchrony, leads to learning new words. To measure this, Nencheva et al. analyzed both overall and moment-to-moment engagement of children who listened to novel words in different pitch contours. Based on the findings of the previous experiment, the researchers selected “hills” as the most engaging and “valleys” as the least engaging. Nencheva et al. found that on average toddlers learned novel words that followed a hill-shaped contour slightly better than those that followed a valley-shaped contour. More importantly, the more engaged a given toddler was with a specific novel word, the more likely they were to learn its meaning. This showed that these very subtle changes in how much toddlers are paying attention from one moment to the next can shape how well they learn in those moments.

The researcher team proposes various hypotheses as to why the hill-shaped contour is the most engaging and leads to better learning outcomes, while the valley-shaped contour is not. The first is that toddlers may learn to associate more interesting or relevant content with CDS prosody overall and especially with hill-shaped contours. The second possible explanation is that caregivers’ speech evolves in response to children’s reactions and it is caregivers wholearn to use the prosody eliciting the highest attention. Further research is needed to make firm conclusions and test the universality of this preference across languages. As for the finding that valley-shaped contours are associated with less engagement and fewer learned words, the researchers speculated that these results may be due to the fact that the valley contour is perceived as sounding “the least natural” in surveys. In comparison, the hill-shaped contour was rated as the most natural-sounding one.

Nencheva et al.’s research is an exciting contribution to studies of child-directed-speech. It uncovers the main prosodic patterns of CDS and shows how toddlers engage with them overall and moment-to-moment. In addition, their research introduces a novel method of measuring engagement with CDS. Most importantly, the team found that in-the-moment attention to pitch dynamics predicts word learning in toddlers and has identified the pitch patterns yielding the best learning outcomes. This study paves the way for more research in moment-to-moment fluctuations in children’s attention and engagement with CDS and opens a new avenue of inquiry in exploring to which degree CDS’s patterns and resulting learning outcomes are universal across the world’s languages. In a conversation with Mira Nencheva, the first author of the study, she expanded on this point:

“We don’t know if they [CDS pitch contours] are universal – they may be, but I suspect they would differ depending on the prominent pitch contours in different languages…[T]his is an open question – do parents present information in a way that adapts to what infants naturally pay attention to or do infants learn to pay attention to what parents do in these prominent moments when important information is presented – likely it’s both. It certainly is a natural next step for this research.”

This original article was published in Developmental Science on May 22, 2020. Please follow this link to view the full version.

Figures