Review written by Crystal Lee (PSY) and Adelaide Minerva (PNI)

Recently, the term “fake news” has been solidified as a colloquial term. Indeed, it seems the world has seen an increase in the spread of misinformation. What is particularly troubling about this trend is that psychology studies show that increased exposure to information (both true and false) increases our beliefs about its truthfulness, and what we believe to be true impacts our behavior in important ways (e.g., voting). When we consider the spread of “fake news”, how do we know what is true, and how do we protect ourselves from misinformation?

Research conducted by Vlasceanu and colleagues at Princeton and Yale Universities sought to answer this question. They took a broad perspective by considering the spread of beliefs throughout a community, rather than to an individual. This approach was critical, as research has shown that individual beliefs are strongly influenced by community-wide spread of information. Specifically, they investigated how public sources (such as a public speaker) and subsequent conversations with others affect community beliefs.

To investigate this question, the authors considered a previously reported phenomenon known as the illusory truth effect. The illusory truth effect is demonstrated through prior studies in which researchers found that individuals are more likely to believe information that they remember/have encountered before whether or not the information is indeed true (e.g., myths such as “Children can outgrow peanut allergies”). This phenomenon is thought to occur due to an up-regulation of memory for information, leading to that information being recalled more easily and thus feeling more believable to an individual. In prior work, Vlasceanu & Coman (2018) extended this research on the illusory effect by investigating whether decreasing memory for a belief can decrease believability. They had participants memorize a list of category-statements (e.g., “Allergy: Children can outgrow peanut allergies”) and had them listen to someone mentioning a subset of these statements during a “selective practice phase.” They found results similar to those of previous studies: participants remembered the practiced statements better and found them to be more believable. Further, they found that statements related to those listened to during the practiced phase, but listened to themselves (e.g., “Allergy: Some babies are allergic to their mother’s milk”) were more likely to be forgotten and were rated as less believable. These findings suggest that what we believe is strongly influenced by both what we remember and what we are able to recall more easily. The 2020 work by Vlaseanu and colleagues, discussed here, extends this finding by examining these results in the context of communities.

In these experiments, Vlasceanu et al. used a two-step communication model, where information was first presented by a public speaker, and then propagated through dyadic (two-person) conversations. Participants were recruited and grouped into networks consisting of 12 people each. The experiment was as follows:

- Participants read statements that were either myths or true. The statements were rated for accuracy and believability.

- In an experimental condition: participants listened to who they believed to be a former participant recalling information from a previous session. Statements were a subset of those read in (1). In a control condition, participants performed an unrelated task.

- All participants were then sequentially paired with one other person within their network and asked to collaboratively remember as many of the initial statements as possible. This structure and flow of information was designed to resemble that of real-world social networks.

- Participants were then asked to rate the believability of randomly selected statements both immediately after the conversation phase of the experiment and one week later.

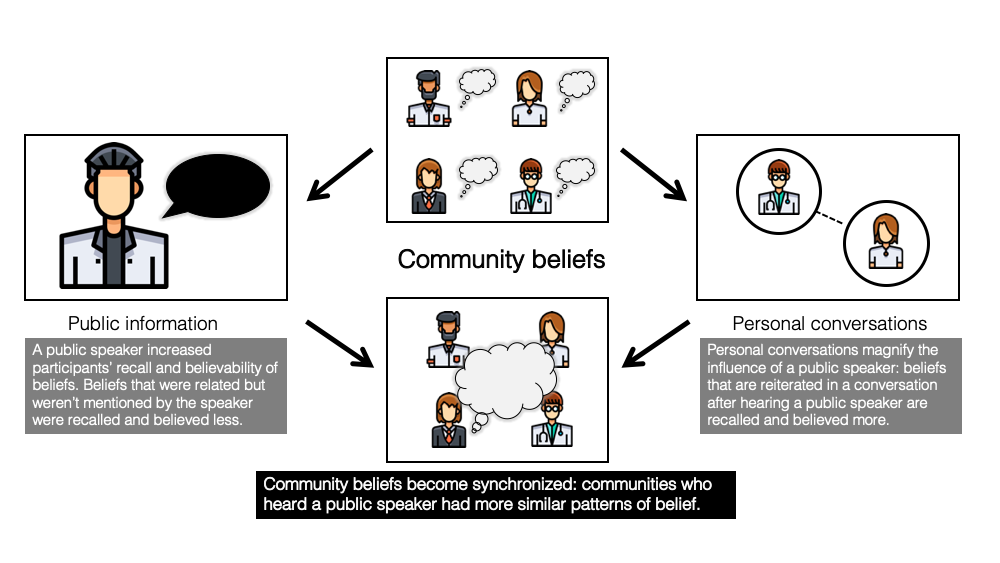

Vlasceanu and colleagues found that listening to beliefs, both true or false, repeated by a public speaker increased participants’ recall and believability of those beliefs, compared to participants who did not have exposure to a speaker. On the other hand, beliefs that were related to but not mentioned by the speaker were recalled less and were rated as less believable by participants. These results are similar to those found in the individual experiment and suggest that public re-exposure to beliefs influences one’s ability to recall, and tendency to believe, those beliefs. In other words, our beliefs are significantly influenced by the public information we encounter.

Furthermore, the influence of a public speaker on beliefs is stronger if we also subsequently engage in interpersonal conversations about those beliefs. The authors found that the impact of the public speaker was stronger if those same statements were mentioned in following dyadic conversations. Specifically, the statements that were repeated by the public speaker and remembered in the following conversation were rated as more believable. The contrary was also true, statements that were not mentioned by the public speaker, but were related to those that were, were not remembered in the following conversations and were believed to be less true.

Finally, the authors explored whether overall beliefs of the participants became synchronized within their 12-person networks. They found that participants who heard the public speaker changed their beliefs in more similar ways than participants who did not have re-exposure to the statements through a speaker. This suggests that a public source (such as a speaker) facilitates community-wide synchronization of beliefs. The influence of a speaker and community spread was long-lasting, with post-experiment belief scores remaining similar even after one week.

Vlasceanu et al.’s work under controlled conditions demonstrates that a public source of information influences community-wide beliefs by promoting memory of those beliefs. The more we hear it, the more believable we think it to be. So how can we combat pervasive misinformation? The results from Vlasceanu and colleagues suggest a simple explanation: by repeatedly offering competing, accurate information, rather than directly refuting false information, the believability of misinformation will decrease across individuals and communities.

Madalina is currently working on other projects to extend the work highlighted here, including a project examining the propagation of COVID-19 information (from scientific facts to conspiracy theories) through online communities. “We suspect the formation of collective beliefs regarding COVID-19 will display different properties given the heightened levels of stress and uncertainty surrounding this topic, but we're curious to see,” she explained.

This original article was published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology on January 30, 2020. Please follow this link to view the full version of the article.